A

run level is a state of init and the whole system that defines

what system services are operating. Run levels are identified by numbers. Some

system administrators use run levels to define which subsystems are working,

e.g., whether X is running, whether the network is operational, and so on.

Others have all subsystems always running or start and stop them individually,

without changing run levels, since run levels are too coarse for controlling

their systems. You need to decide for yourself, but it might be easiest to

follow the way your Linux distribution does things. The following table defines

how most Linux Distributions define the different run levels. However, run-levels

2 through 5 can be modified to suit your own tastes.

|

0

|

Halt the system.

|

|

1

|

Single-user mode (for special

administration).

|

|

2

|

Local Multiuser with Networking

but without network service (like NFS)

|

|

3

|

Full Multiuser with Networking

|

|

4

|

Not Used

|

|

5

|

Full Multiuser with Networking and

X Windows(GUI)

|

|

6

|

Reboot.

|

Table: Run-Levels in Linux

When

a Linux system boots, it enters its default run level and runs the startup

scripts associated with that run level. You can also switch between run levels

– for example, there’s a run level designed for recovery and maintenance operations.

Fig1:

Readme File

Traditionally,

Linux used System V-style init scripts – while new init systems will eventually

obsolete traditional run levels, they haven’t yet. For example, Ubuntu’s

Upstart system still uses traditional System V-style scripts. "Runlevel"

defines the state of the machine after boot. Different runlevels are typically

assigned to:

- Single-user mode

- Multi-user mode without network services started

- Multi-user mode with network services started

- System shutdown

- System reboot

What is a Run level?

When

a Linux system boots, it launches the init processes. init is

responsible for launching the other processes on the system. For example, when

you start your Linux computer, the kernel starts init, and init executes the

startup scripts to initialize your hardware, bring up networking, and start

your graphical desktop.

However,

there isn’t just one single set of startup scripts init executes. There are

multiple run levels with their own startup scripts – for example, one run level

may bring up networking and launch the graphical desktop, while another run

level may leave networking disabled and skip the graphical desktop. This means

you can drop from “graphical desktop mode” to “text console mode without

networking” with a single command, without manually starting and stopping

different services.

More

specifically, init runs the scripts located in a specific directory that

corresponds to the run level. For example, when you enter run level 3 on

Ubuntu, init runs the scripts located in the /etc/rc3.d directory.

Fig2:rc3d File

At

least, this is how it works with a traditional System V init system – Linux

distributions are beginning to replace the old System V init system. While

Ubuntu’s Upstart currently maintains compatibility with SysV init scripts, this

is likely to change in the future.

Run levels:

Some

run levels are standard between Linux distributions, while some runlevels vary

from distribution to distribution.

The

following runlevels are standard:

- 0 – Halt (Shuts down the system.)

- 1 – Single User Mode (The system boots into super user mode without starting daemons or networking. Ideal for booting into a recovery or diagnostics environment.)

- 6 – Reboot

Run

levels 2-5 vary depending on distribution. For example, on Ubuntu and Debian, run

levels 2-5 are the same and provide a full multi-user mode with networking and

graphical login. On Fedora and Red Hat, runlevel 2 provides multi-user mode

without networking (console login only), runlevel 3 provides multi-user mode

with networking (console login only), runlevel 4 is unused, and runlevel 5

provides multi-user mode with networking and graphical login.

Switching to a Different Runlevel:

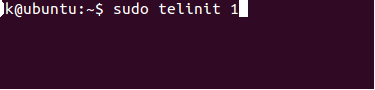

To

switch to a different runlevel while the system is already running, use the

following command:

sudo telinit

#

Replace

# with the number of the runlevel you want to switch to. Omit sudo and run the

command as root if you’re running a distribution that doesn’t use sudo.

Fig3:Terminal window

Booting Directly to a Specific Runlevel:

You

can select a runlevel to boot into from the boot loader – Grub, for example. At

the start of the boot process, press a key to access Grub, select your boot

entry, and press e to edit it.

Fig4:Login window

You

can add single to the end of the Linux line to enter the

single-user runlevel (runlevel 1). (Press Ctrl+x to boot after.) This is the

same as the recovery mode option in Grub.

Fig5:Mode verify

Traditionally,

you could specify a number as a kernel parameter and you’d boot to that

runlevel – for example, using 3 instead of single to boot to

runlevel 3. However, this doesn’t appear to work on the latest versions of

Ubuntu – Upstart doesn’t seem to allow it. Similarly, how you change the

default runlevel will depend on your distribution.

While

Ubuntu’s Upstart daemon still emulates the SystemV init system, much of this

information will change in the future. For example, Upstart is event-based – it

can stop and start services when events occur (for example, a service could

start when a hardware device is connected to the system and stop when the

device is removed.) Fedora also has its own successor to init, systemd.