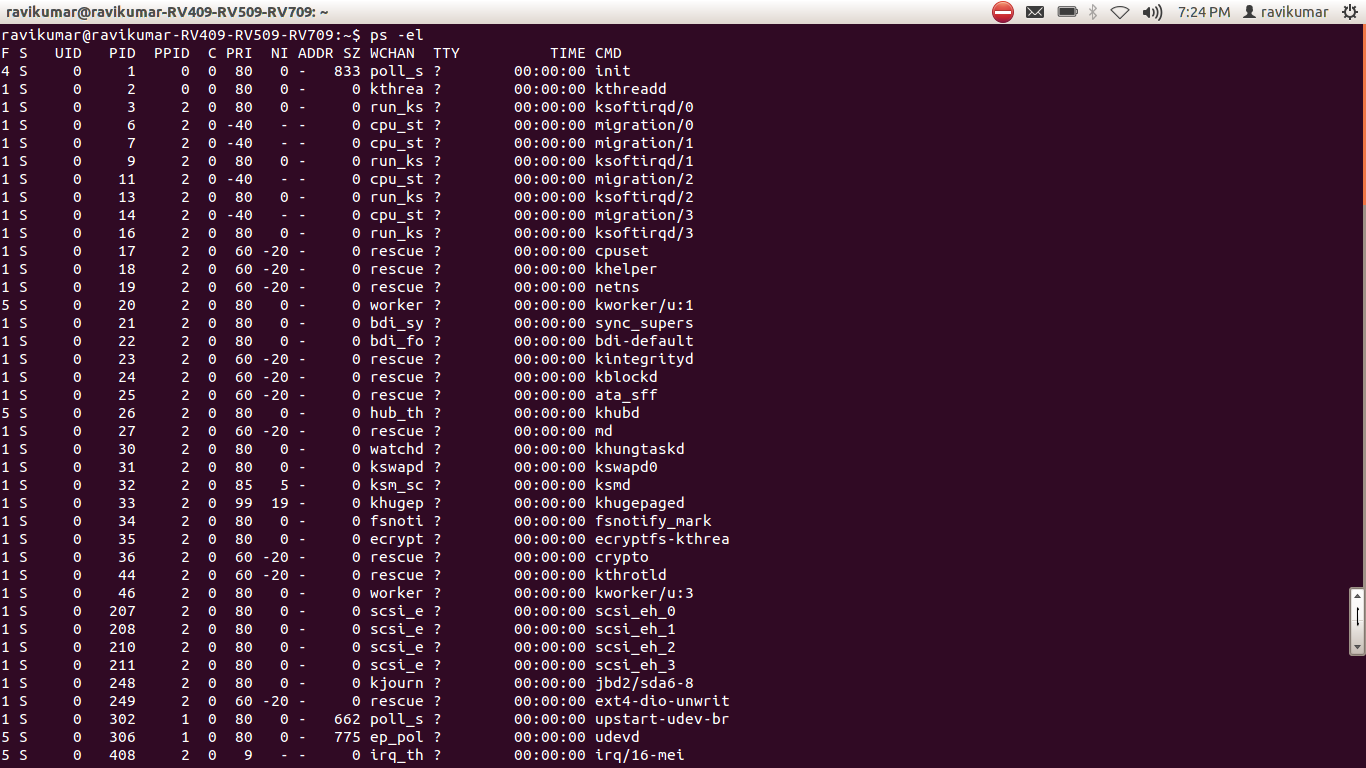

A shell

is a command-line interpreter or shell that provides a traditional user

interface for the UNIX operating system and for Unix-like systems. Users direct

the operation of the computer by entering commands as text for a command line

interpreter to execute or by creating text scripts of one or more such

commands. The versatility of the command-line shell is what really allows this,

but what makes each shell different and why do people prefer one over another?

Fig1: Shells in Linux

The most influential UNIX shells have been

the Bourne shell and the C shell. The Bourne shell, sh, was written by Stephen

Bourne at AT&T as the original UNIX command line interpreter; it introduced

the basic features common to all the UNIX shells, including piping, here

documents, command substitution, variables, control structures for

condition-testing and looping and filename wildcarding. The language, including

the use of a reversed keyword to mark the end of a block, was influenced by ALGOL

68. The C shell, csh, was written by Bill Joy while a graduate student at University

of California, Berkeley. The language, including the control structures and the

expression grammar, was modeled on C. The C shell also introduced a large

number of features for interactive work, including the history and editing

mechanisms, aliases, directory stacks, tilde notation, cdpath, job control and path

hashing.

Users typically interact with a modern UNIX

shell using a terminal emulator. Common terminals include xterm and GNOME

Terminal. Both shells have been used as coding base and model for many

derivative and work-alike shells with extended feature sets.

What Do Shells Do?

The command-line is a very interesting

thing. Once considered to be the most advanced user interface, it has gone the

way of waistcoats and fountain pens: shunned to the periphery. While you still

see much of the purpose and utility in them, they’re usually left aside

primarily for enthusiasts to appreciate, mainly because they spend the time to

learn the ins and outs of them. Indeed, the command-line in any given operating

system will have a lot of quirks because easy OS interprets commands

differently. Today, this is mainly an issue between Linux, OS X, and Windows,

but before this was a problem with most computers.

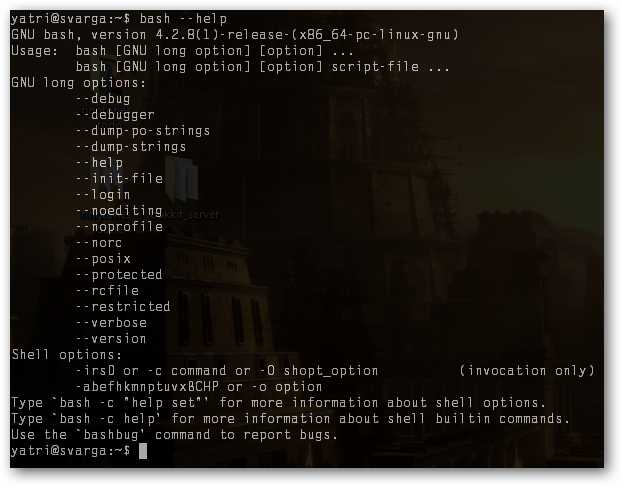

Fig2: Shell types

Shells entered the picture and allowed a more

standard extension of the command-line in a way that was much more

inconspicuous. Shells added a lot of functionality, such as command and file

name completion and more advanced scripting abilities, and helped bring some

performance enhancements. They also did a lot to cover some annoying problems.

For example, in Unix, you couldn’t back up through symlinks to the directories

before you followed them. All in all, they added some features that allowed

users to get their jobs done more quickly and efficiently, just like Linux’s

plethora of alternative Window Managers.

Why Are There So Many?

The most prominent progenitor of modern

shells is the Bourne shell – known as ‘sh’ – which was named after its creator

Stephen Bourne who worked at AT&T. It became the default UNIX

command-interpreter because of its support for command substitution,

piping, variables, condition-testing, and looping, along with other features.

This was in an era that programming really went along with using the

command-line, a practice that many argue has been diluted today. It did not

offer users much leeway in customizations for users, such as aliases, command

completion and shell functions.

Fig3: Shell varieties

C shell (‘csh’) was developed Bill Joy at UCB

and really shook things up. It added a lot of interactive elements that users

could use to control their systems, like aliases (shortcuts for long commands),

job management abilities, command history, and more. It was modeled off of the

C programming language, an interesting idea because UNIX was written in C. It

also meant that users of the Bourne shell had to learn C so they could enter

commands in it. In addition, it had tons of bugs which had to be hammered out

by users and creators alike over a large period of time. People ended up using

the Bourne shell for scripts because it handled non-interactive commands

better, but stuck with the C shell for normal use.

Over time, lots of people fixed the bugs in and

added features to the C shell, culminating in something called ‘tcsh’. The

problem, then, was that in distributed Unix-based computers, csh was still the

default, and had some added “non-standard” features added in, creating a very

fragmented mess of things (in retrospect). Then, David Korn from AT&T

worked on the Korn shell – ‘ksh’ – which tried to mitigate the situation by

using the Bourne shell’s language as a basis, but added in all of the new

features that everyone was accustomed to. Unfortunately for many, it wasn’t

free.

Fig4: tcsh

Another response to the hectic proprietary

csh implementations was the Portable Operating System Interface for UNIX, or

POSIX. It was a successful attempt at creating a standard for command

interpretation and eventually mirrored a lot of the features that the Korn

shell had. Simultaneously, the GNU project was going on and was an attempt at

creating a free operating system that was completely Unix-compatible. It

developed a shell for its own purpose: the Bourne Again shell, formed by

bashing together features from sh, csh, and ksh. The result, as seen in

retrospect, was pretty impressive.

Kenneth Almquist created a Bourne shell clone

– ‘ash’ – that was POSIX-compatible and would become the default shell in BSD,

a different branch/clone of UNIX. Its uniqueness is that it’s really

lightweight, so it became extremely popular in embedded-Linux systems. If you

have a rooted Android phone that has Busy Box installed, it’s using code from

ash. Debian developed a clone based on ash called ‘dash’.

Fig5: Ash

One of the most prominent of “new” shells is

‘zsh’, developed by Paul Falstad in 1990. It’s a Bourne-style shell that takes

features from bash and previous shells and adds even more features. It has

spell-checking, the ability to watch for logins/logouts, some built-in

programming features like bytecode, support for scientific notation in syntax,

allows for floating-point arithmetic, and then some. Another is the Friendly

Interactive Shell, ‘fish’, which focuses on command syntax that’s easy to

remember and use.

On the whole, most shells were created as

clones of previous shells that added functionality, fixed bugs, and bypassed

licensing issues and fees. The notable exceptions are the original Bourne shell

and the C shell, and both rc shell and ash which aren’t entirely original but

definitely have some niche-utility.

Which Should I Use?

With so many out and about, you’d think that

it’s hard to choose which shell to use, but it’s actually not very difficult.

Since so many are based off of Bourne shell, basic things will be the same

between most shells.

Fig6: Shell choices

Bash is the most widely used shell out there

and is the default for most Linux distributions. It’s really robust and has

tons of features, most of which you probably won’t use unless you program, so

it’s pretty safe to say you can stick to this one. Because it’s so common, it’s

perfect for scripting things that will be used across different platforms. If

you want to try something different that’s a little more user-friendly, you can

try out fish instead.

If you tinker with embedded-Linux systems a

lot, like to put Linux on ridiculous things like your Nintendo DS, or you

really like Debian, then ash/dash is probably best suited for you. Again, it

works mostly like the others, but since it’s sort of bare-bones and

light-weight, you’ll find some more complicated functionality missing.

Fig7: Zsh

If you plan on programming or learning to

develop on the command-line, then you’ll have to be a little choosier. Bash is

a fine choice, but I know enough people who have switched to Zsh for its

extras. I guess it really depends on how complicated your projects will get and

what type of functionality you prefer from your shell. Some people still stick

to tcsh because they know and use C regularly and it’s easier for them. Odds

are that if you’re not sure which shell to choose, you probably don’t program

much, so try to choose something that will line up with what you want to learn

and do some research on what others in that field use.

You can easily install and remove different

shells using the Software Center on Ubuntu or your preferred package manager.

Shells are located in the /bin/ directory, and as long as you’re running a

modern Linux distribution, it’s easy to change what your default is. Just enter

the following command:

- chsh

You’ll be prompted for your password, and

then you can change to a different shell by entering its path.

Fig8: Chsh

In square brackets, you’ll see your current

default, and if you want to leave it as-is, just hit Enter.

So guys, which shells you use or prefer? Do

comment.

.png)

.png)

.png)